Why Jacobites:-

Jacobitism was a political movement in Great Britain and Ireland that aimed to restore the Roman Catholic Stuart King, James II of England and Ireland (James VII of Scotland) and his heirs to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland. The movement took its name from "Jacobus" the Renaissance Latin form of Iacomus, which in turn comes from the original Latin form of James "Iacobus."

Causes:-

From the second half of the 17th century onwards, a time of political and religious turmoil existed in the kingdoms. The Commonwealth ended with the Restoration of Charles II. During his reign the Church of England was re-established, and episcopal church government was restored in Scotland. The latter move was particularly contentious, causing many, especially in the south-west of Scotland, to abandon the official church, attending illegal field assemblies known as 'conventicles' in preference. The authorities attempted some accommodation with Presbyterian dissidents, introducing official 'Indulgences' in 1669 and 1672, meeting with some limited success. Towards the end of Charles's reign those with more radical Presbyterian opinions, known as the Covenanters, who favoured rejecting all compromise with the state, began to move away from religious dissent to outright political sedition. This was particularly true of the followers of the Reverend Richard Cameron, soon to be known as the Cameronians. The government increasingly resorted to force in its attempts to stamp out the Cameronians and the other Society Men, in a period subsequently labelled as the Killing Time.

Since the late Middle Ages, the Kingdoms of England and Scotland had been evolving towards a quasi-oligarchical or collegiate form of government in which the monarch was held to rule with the consensus of the land-owning upper classes.

The reigns of the last three Stuart Kings – Charles I, Charles II and James II and VII – were marked by growing Royal resistance to this developing consensual model of government. In part the Kings were inspired by the development of Royal Absolutism in contemporary Europe, exemplified particularly strongly by their neighbour and contemporary, Louis XIV of France. In part, however, the apologists of royal authority based their claims on a just assessment of the powers claimed by England and Scotland's medieval monarchs.

In 1685, Charles II was succeeded by his Roman Catholic brother, James II and VII. In addition to sharing his family's absolutist views of government, James attempted to introduce religious toleration of Roman Catholics and Protestant Dissenters. In Seventeenth-century Europe, being a religious outsider meant being a political and social outsider as well. James tried to encourage the participation in public life of Roman Catholics, Protestant Dissenters, and Quakers such as William Penn the Younger. Such attempts to broaden his basis of support succeeded in antagonising members of the Anglican establishment.

In Ireland, James's viceroy, Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, was the first Catholic viceroy since the Reformation and acted to reduce Protestant ascendancy and to garrison Irish military outposts with troops loyal to the views of James.

In England and Scotland, James attempted to impose religious toleration, which helped the Catholic minority but alarmed the religious and political establishment. William of Orange, building alliances against France, lobbied the English political élite to have James replaced by William's wife Mary who was James's daughter and next in line to the throne, but they were reluctant to rush a succession expected to happen in due course. Then in 1688 James's second wife had a boy, bringing the prospect of a Catholic dynasty, and the "Immortal Seven" (Seven notable Englishmen, Earl of Shrewsbury, Earl of Devonshire, Ear of Danby, Viscount Lumley, Bishop of London, Edward Russell and Henry Sydney) invited William and Mary to depose James. On 4 November 1688 William arrived at Torbay, England. When he landed the next day, at Brixham, James fled to France. In February 1689, the Glorious Revolution formally changed England's monarch, but many Catholics, Episcopalians and Tory royalists still supported James as the constitutionally legitimate monarch.

After James II was deposed in 1688 by Mary and William (James's nephew), the Stuarts lived in exile, occasionally attempting to regain the throne.

The Jacobites believed that Parliamentary interference with the line of succession to the English and Scottish thrones was illegal. Catholics also hoped the Stuarts would end recusancy (Roman Catholics in England who incurred legal and social penalties for refusing to attend services of the Church of England). In Scotland, the Jacobite cause became intertwined with the clan system.

Jacobite Strongholds:-

The strongholds of Jacobitism were parts of the Scottish Highlands, and the low land north-east of Scotland, Ireland, and parts of Northern England (mostly within the counties of Northumberland and Lancashire). Significant support also existed in Wales and South-west England.

Jacobite Ideology:-

Jacobite ideology comprised four main tenets: The divine right of kings, the "accountability of Kings to God alone", inalienable hereditary right, and the "unequivocal scriptural injunction of non-resistance and passive obedience", though these positions were not unique to the Jacobites. What distinguished Jacobites from Whigs was their adherence to 'right' as the basis for the law, whereas the Whigs held to the idea of 'possession' as the basis of the law. However, such distinctions became less clear over time, with an increase in the use of contract theory by some Jacobite writers during the reign of George I.

Jacobites contended that James II had not been legally deprived of his throne, and that the Convention Parliament and its successors were not legal. Scottish Jacobites resisted the Act of Union of 1707; while not recognising Parliamentary Great Britain, Jacobites recognised their monarchs as Kings of Great Britain.

The majority of Irish people supported James II due to his 1687 Declaration of Indulgence or, as it is also known, The Declaration for the Liberty of Conscience, which granted religious freedom to all denominations in England and Scotland, and also due to James II's promise to the Irish Parliament of an eventual right to self-determination.

Jacobite Community and Policy:-

From its religious roots, Jacobite ideology was passed on through committed families of the nobility and gentry who would have pictures of the exiled royal family and of Cavalier and Jacobite martyrs, and take part in like minded networks. Even today, some Highland clans and regiments pass their drink over a glass of water during the Loyal Toast – to the King Over the Water. More widely, commoners developed communities in areas where they could fraternise in Jacobite alehouses, inns and taverns, singing seditious songs, collecting for the cause and on occasion being recruited for risings. At government attempts to close such places they simply transferred to another venue. In these neighbourhoods Jacobite wares such as inscribed glassware, brooches with hidden symbols and tartan waistcoats were popular. The criminal activity of smuggling became associated with Jacobitism throughout Britain, partly because of the advantage of dealing through exiled Jacobites in France.

Official policy of the court in exile initially reflected the uncompromising intransigence that got James into trouble in the first place. With the powerful support of the French they saw no need to accommodate the concerns of his Protestant subjects, and effectively issued a summons for them to return to their duty. In 1703 Louis pressed James into a more accommodating stance in the hopes of detaching England from the Grand Alliance, essentially promising to maintain the status quo. This policy soon changed, and increasingly Jacobitism ostensibly identified itself with causes of the alienated and dispossessed.

The Old Pretender:-

After the death of James II in 1701, the Jacobite claim to the thrones of Scotland and England was taken up by his only surviving legitimate son, James Francis Edward Stuart (1688–1766). His supporters proclaimed him James III of England and Ireland, and James VIII of Scotland. The French king Louis XIV and Pope Clement XI formally recognised the Catholic monarch as King James III & VIII. Later, James was called "the Old Pretender", to distinguish him from his son, Charles Edward Stuart (1720–1788), who became known as "the Young Pretender".

The Rising Of 1715 ("the Fifteen"):-

Following the arrival from Hanover of George I in 1714, Tory Jacobites in England conspired to organise armed rebellions against the new Hanoverian government. They were indecisive and frightened by government arrests of their leaders. In Scotland 1715, is sometimes misleadingly called the first Jacobite rebellion (or rising), which overlooks the fact that there had already been a major Jacobite rising in 1689 .

The Treaty of Utrecht ended hostilities between France and Britain. From France, as part of widespread Jacobite plotting, James Stuart, the Old Pretender, had been corresponding with the Earl of Mar. In the summer of 1715, James called on Mar to raise the Clans. Mar, nicknamed Bobbin' John, rushed from London to Braemar. He summoned clan leaders to "a grand hunting-match" on 27 August 1715. On 6 September he proclaimed James as "their lawful sovereign" and raised the old Scottish standard. Mar's proclamation brought in an alliance of clans and northern Lowlanders, and they quickly overran many parts of the Highlands.

Mar's Jacobites captured Perth on 14 September, without opposition. His army grew to around 8,000 men. A force of fewer than 2,000 men under the Duke of Argyll held the Stirling plain for the government and Mar indecisively kept his forces in Perth. He waited for the Earl of Seaforth to arrive with a body of northern clans. Seaforth was delayed by attacks from other clans loyal to the government. Planned risings in Wales, Devon and Cornwall were forestalled by the government arresting the local Jacobites.

Starting around 6 October, a rising in the north of England grew to about 300 horsemen under Thomas Forster, a Northumberland squire and MP. This English contingent contained some prominent people, including two peers of the realm, James Ratcliffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater, and Lord Widdrington, and a future peer, Charles Ratcliffe, later fifth Earl of Derwentwater. (Another future English peer, Edward Howard, later 9th Duke of Norfolk, joined the rising in Lancashire). They joined forces with a rising in the south of Scotland under Viscount Kenmure. Mar sent a Jacobite force under Brigadier William Mackintosh of Borlum to join them. They left Perth on 10 October, and were ferried across the Firth of Forth from Burntisland to East Lothian. Here they were diverted into an attack on an undefended Edinburgh, but having seized Leith citadel they were chased away by the arrival of Argyll's forces. Mackintosh's force of about 2,000 then made their way south and met their allies at Kelso in the Scottish Borders on 22 October, and spent a few days arguing over their options. The Scots wanted to fight government forces in the vicinity or attack Dumfries and Glasgow, but the English were determined to march towards Liverpool and led them to expect 20,000 recruits in Lancashire.

The Highlanders resisted marching into England and there were some mutinies and defections, but they pressed on. Instead of the expected welcome the Jacobites were met by hostile militia armed with pitchforks and very few recruits. They were unopposed in Lancaster and found about 1,500 recruits as they reached Preston on 9 November, bringing their force to around 4,000. Then Hanoverian forces (including the Cameronians) arrived to besiege them at the Battle of Preston. The Jacobites actually won the first day of the battle, killing large numbers of Government forces. However, Government reinforcements arrived, and the Jacobites surrendered on 14 November.

In Scotland, at the Battle of Sheriffmuir on 13 November, Mar's forces were unable to defeat a smaller force led by the Duke of Argyll and Mar retreated to Perth while the government army built up. On 22 December 1715 a ship from France finally brought the Old Pretender to Peterhead in person. But an ailing James proved far too timid and melancholy to inspire his followers. He briefly set up court at Scone, Perthshire, visited his troops in Perth and ordered the burning of villages to hinder the advance of the Duke of Argyll through deep snow. The highlanders were cheered by the prospect of battle, but James's counsellors decided to abandon the endeavour and ordered a retreat to the coast, giving the pretext of seeking a stronger position. James boarded a ship at Montrose and escaped to France on 4 February 1716, leaving a message assigning his Highland adherents to shift for themselves.

Aftermath of the "Fifteenth":-

In the aftermath of the 'Fifteen', the Disarming Act and the Clan Act made some attempts to subdue the Scottish Highlands. Government garrisons were built or extended in the Great Glen at Fort William, Kiliwhimin (later renamed Fort Augustus) and Fort George, Inverness, as well as barracks at Ruthven, Bernera (Glenelg) and Inversnaid, linked to the south by the Wade roads constructed for Major-General George Wade.

On the whole, the government adopted a gentle approach and attempted to 'win hearts and minds' by allowing the bulk of the defeated rebels to slip away back to their homes and committing the first £20,000 of revenue from forfeited estates to the establishment of Presbyterian-run, Scots-speaking schools in the Highlands (the latest in a series of measures intended to promote Scots at the expense of Scottish Gaelic) and Presbyterianism at the expense of Episcopalianism and Roman Catholicism.

The Young Pretender:-

In 1743 the War of the Austrian Succession drew Britain and France into open, though unofficial, hostilities against each other. Leading English Jacobites made a formal request to France for armed intervention and the French king's Master of Horse toured southern England meeting Tories and discussing their proposals. In November 1743 Louis XV of France authorised a large-scale invasion of southern England in February 1744 which was to be a surprise attack. Troops were to march from their winter quarters to hidden invasion barges which were to take them and Charles Edward Stuart, with the guidance of English Jacobite pilots to Maldon in Essex where they were to be joined by local Tories in an immediate march on London. Charles, (later known as Bonnie Prince Charlie or the Young Pretender) was in exile in Rome with his father (James Stuart, the Old Pretender), and rushed to France.

As late as 13 February the British were still unaware of these intentions, and while they then arrested many suspected Jacobites the French plans really went astray on 24 February when one of the worst storms of the century scattered the French fleets which were about to battle for control of the English Channel, sinking one ship and putting five out of action.

The barges had begun embarking some 10,000 troops and the storm wrecked the troop and equipment transports, sinking some with the loss of all hands. Charles was officially informed on 28 February that the invasion had been cancelled. The British lodged strong diplomatic objections to the presence of Charles, and France declared war but gave Charles no more support.

The Rising of 1745 (the Forty-five):-

Charles continued to believe that he could reclaim the kingdom and recalled that early in 1744 a few Scottish Highland clan chieftains had sent a message that they would rise if he arrived with as few as 3,000 French troops. Living at French expense, he continued to petition ministers for commitment to another invasion, to their increasing irritation. In secrecy he also developed a plan with a consortium of Nantes privateers, funded by exiled Scots bankers and pawning of his mother's jewelry. They fitted out the 16-gun privateer Du Teillay and a ship of the line the Elisabeth and set out from Nantes for Scotland in July 1745 on the pretence that this was a normal privateering cruise, leaving a personal letter from Charles to Louis XV of France announcing the departure and asking for help with the rising. The Elisabeth, carrying weapons, supplies and 700 volunteers from the Irish Brigade, encountered the British Navy ship HMS Lion and with both ships badly damaged in the ensuing battle the Elisabeth was forced back, but the Du Teillay successfully landed Charles with his seven men of Moidart on the island of Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides on 2 August 1745.

The Scottish clans and their chieftains initially showed little enthusiasm about his arrival without troops or munitions (with Alexander MacDonald of Sleat and Norman MacLeod of MacLeod refusing even to meet with him), but Charles went on to Moidart and on 19 August 1745 raised the standard at Glenfinnan to lead the second Jacobite rising in his father's name. This attracted about 1,200 men, mostly of Clan MacDonald of Clan Ranald, Clan MacDonell of Glengarry, Clan MacDonald of Keppoch, and Clan Cameron. The Jacobite force marched south from Glenfinnan, increasing to almost 3,000 men, though two chieftains insisted on pledges of compensation before joining.

Britain was still in the midst of the War of the Austrian Succession and most of the British army was in Flanders and Germany, leaving an inexperienced army of about 4,000 in Scotland under Sir John Cope. His force marched north into the Highlands but, believing the rebel force to be stronger than it really was, avoided an engagement with the Jacobites at the Pass of Corryairack and withdrew northwards to Inverness. The Jacobites captured Perth and at Coatbridge on the way to Edinburgh routed two regiments of the government's Dragoons. In Edinburgh there was panic with a melting away of the City Guard and Volunteers and when the city gate at the Netherbow Port was opened at night, to let a coach through, a party of Camerons rushed the sentries and seized control of the city. The next day King James VIII was proclaimed at the Mercat Cross and a triumphant Charles entered Holyrood palace.

Cope's army got supplies from Inverness then sailed from Aberdeen down to Dunbar to meet the Jacobite forces near Prestonpans to the east of Edinburgh. On 21 September 1745 at the Battle of Prestonpans a surprise attack planned by Lord George Murray routed the government forces, as celebrated in the Jacobite song 'Hey, Johnnie Cope, Are Ye Waking Yet?'. Charles immediately wrote again to France pleading for a prompt invasion of England. There was alarm in England, and in London a patriotic song which included a prayer for Marshal Wade's success in crushing the rebels was performed, later to become the National Anthem.

The Jacobites held the city of Edinburgh, though not the castle. Charles held court at Holyrood palace for five weeks amidst great admiration and enthusiasm, but failed to raise a regiment locally. Many of the highlanders went home with booty from the battle and recruiting resumed, though Whig clans opposing the Jacobites were also getting organised. The French now sent some weapons and funds, and assurances that they would carry out their invasion of England by the end of the year. Charles's Council of war led by Murray was against leaving Scotland, but he told them that he had received English Tory assurances of a rising if he appeared in England in arms, and the Council agreed to march south by a margin of one vote.

Success at Prestonpans had not, as is often claimed, left the rebels in control of Scotland, for the great bulk of the population remained bitterly hostile to the absolutist Stuarts who, prior to their expulsion in a popular revolution, had presided over the notorious persecutions known as Scotland's 'Killing Times'. Many Scottish burghs offered burgess status to any man who would volunteer to fight against the Jacobites and, when the rebels passed near the town of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire, local loyalists mounted a raid on their baggage train.

The Jacobite army of under six thousand men had set out and an army under General George Wade assembled at Newcastle. Charles wanted to confront them, but on the advice of Lord George Murray and the Council they made for Carlisle and successfully bypassed Wade. At Manchester about 250 Episcopalians formed a regiment, and a number of other Englishmen had joined the Prince, mainly from rural Lancashire. One Englishman, John Daniel, from the upper echelons of the yeoman class, brought in 39 recruits by himself. A Scotsman who was in the Jacobite army and therefore an eyewitness, wrote home that 60 English recruits had joined in just one day at Preston. The myth that no Englishmen joined the Prince is just that, a myth. At the end of November French ships arrived in Scotland with 800 men from the Écossais Royeaux (Royal Scots) and Irish Regiments of the French army.

The Jacobite army, now reduced by desertions to under 5,000 men, was manoeuvred by Murray round to the east of a second government army under the Duke of Cumberland and marched on Derby.

They entered Derby on 4 December, only 125 miles (200 km) from London, with a resentful Charles by then barely on speaking terms with Murray. Charles was advised of progress on the French invasion fleet which was then assembling at Dunkirk, but at his Council of War he was forced to admit to his previous lies about assurances. While Charles was determined to press on in the deluded belief that their success was due to soldiers of the regulars never daring to fight against their true prince, his Council and Lord George Murray pointed out their position. The promised English support had not materialised, both Wade and Cumberland were approaching, London was heavily defended and there was a fictitious report from a government double agent of a third army closing on them.

They insisted that their army should return to join the growing force in Scotland. This time only Charles voted to continue the advance, and he assented while throwing a tantrum and vowing never to consult the Council again. On 6 December, the Jacobites sullenly began their retreat, with a petulant Charles refusing to take any part in running the campaign which was fortunate given the excellent leadership of Murray, whose brilliant feints and careful planning extracted the army virtually intact. The French got news of the retreat and cancelled their invasion which was now ready, while English Tories who had just sent a message pledging support if Charles reached London went to ground again.

There was a rearguard action to the north of Penrith. The Manchester Regiment was left behind to defend Carlisle and after a siege by Cumberland had to surrender, to face hanging or transportation. Many died in Carlisle Castle, where they were imprisoned in brutal conditions along with Scots prisoners whom Morier allegedly painted to depict the kilted clansmen in battle. Many of the cells there still show hollows licked into the stone walls, as prisoners had only the damp and moss on these stones to sustain themselves. The Young Pretender had his headquarters at the County Hotel during a 3-day sojourn in Dumfries towards the end of 1745. £2,000 was demanded by the Prince, together with 1,000 pairs of brogues for his kilted Jacobite rebel army, which was camping in a field not one hundred yards distant. A rumour, however, that the Duke of Cumberland was approaching, made Bonnie Prince Charlie decide to leave with his army, with only £1,000 and 255 pairs of shoes having been handed over.

By Christmas the Jacobites came to Glasgow and forced the city to re-provision their army, then on 3 January left to seize the town of Stirling and begin an ineffectual siege of Stirling Castle. Jacobite reinforcements joined them from the north and on 17 January about 8,000 of Charles's 9,000 men took the offensive to the approaching General Henry Hawley at the Battle of Falkirk and routed his forces.

The Jacobite army then turned north, losing men and failing to take Stirling Castle or Fort William but taking Fort Augustus and Fort George in Inverness by early April. Charles now took charge again, insisting on fighting an orthodox defensive action, and on 16 April 1746 they were finally defeated near Inverness at the Battle of Culloden by government forces made up of English and Scottish troops and Campbell militia, under the command of the Duke of Cumberland. The seemingly suicidal Highland sword charge against cannon and muskets had succeeded when launched against unprepared or disordered troops in earlier battles but failed now that it was pitted against regulars who had time to form their ranks properly. Charles promptly abandoned his army, blaming everything on the treachery of his officers, even though after the defeat the stragglers and unengaged units rallied at the agreed rendezvous and only dispersed when ordered to leave.

Charles fled to France making a dramatic if humiliating escape disguised as a "lady's maid" to Flora MacDonald. Cumberland's forces crushed the uprising and effectively ended Jacobitism as a serious political force in Britain. The decline of Jacobitism left Charles making futile attempts to enlist assistance, and another abortive plot to raise support in England.

York's Reaction to the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715

The impact of the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715 in York is largely overlooked. There was activity, however, by both the City Corporation and the Church in opposition to it. There was also some Jacobite activity within the city itself, before and after the rebellion.

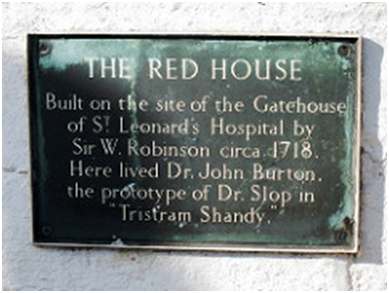

Virtually nothing has been written about York during the 1715 Rebellion. York historians scarcely mention it. Ward states that little happened between 1688 and 1745.(A. Ward "History and antiquities of York" Vol. I [1785] P.M.Tillot ed., V.C.H. City of York [1961 p211, 241). The "Victoria County History" records more; namely that a system of watchmen was established and that the Corporation was hostile to the rebellion. Aveling, in his study of Catholicism in York, does refer to the anti-Catholic measures taken, but prefaces this with the statement: "The 1715 Jacobite Rebellion made relatively little impact on York". (J.C.H.Aveling, "Catholic Recusancy in York, 1558-1791,[1970] p112). As he states, military operations bypassed the city, as in the Forty Five, there was activity in the city regarding the rebellion. This oversight may be, apart from the general neglect of the Fifteen in favour of the Forty Five, because of the scarcity of source material. Unlike the later rebellion, there was no regional press, no long run of correspondence and only a little surviving matter in the State Papers. However, although material is scanty, it does exist.

York was at the centre of the revolt in the North against James II in 1688. The authority of the Catholic Stuart King then rested with Sir John Reresby who was Governor. He was imprisoned by dissident nobility and gentry led by Danby. There were also popular anti-Catholic demonstrations in the city. In 1715, the city was still Whiggish politically and was to remain so until 1734, electing two Whigs as the city MPs in the 1715 General Election. York would, therefore, seem to have been a Whig stronghold, though matters did not go entirely smoothly for them during the subsequent year. (A. Browning ed., "Memoirs of Sir John Reresby [1936], p525-531, R. Sedgwick, "History of Parliament: The Commons", 1715-1754, Vol. I, [1970] p364).

On the death of Queen Anne, the new sovereign, George I, who was also Elector of Hanover as well as King of Great Britain, was proclaimed in York as he was elsewhere. This was done at 8.00 pm., on 4 August 1714, by William Readman, the Lord Mayor, accompanied by Sir William Dawes, Archbishop of York, together with: "the Dean and his brother with a vast concourse of gentlemen.....Aldermen and Common Council". (The Daily Courant, 3996, 13 August 1714). According to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the initial response of the York citizens to the announcement of the Hanoverian Succession was a favourable one. She wrote to her husband in early August that there were: "vast acclamations and the appearance of a general satisfaction, the Pretender afterwards dragged about the streets and burnt, ringing of bells, bonfires and illuminations, the mob crying liberty and property and long live King George". (R. Halsband ed. "Correspondence of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Vol. I, Oxford, (1965), p213).

The Daily Courant likewise testified to the universal joy. (The Daily Courant, 3996, 13 August 1714). Many, however, also felt alarm about the potential danger from without. Lady Mary noted that "attempts from Scotland" were a cause of much alarm, and three days later mentioned that there was concern about a fleet being sent from Scotland. William Dawes, as Archbishop, along with many others, had gone to London, presumably to welcome the new monarch in person. She was, however, reasonably sure of the loyalty of those within the gates of York: "all Protestants here seem unanimous for the Hanover Succession". ((R. Halsband ed. "Correspondence of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Vol. I, Oxford, (1965), p213, 215-215).

The Government was certainly concerned about the potential Jacobite threat to the new Hanoverian dynasty The Lord Mayor was not slow to respond to instructions from central Government. On 11 August 1714, he sent a letter to London, reporting on the action he and his officers had taken. According to him: "We immediately took all precautions imaginable for the security of the peace by locking up the gates here and hindring all suspect persons from going out the next morning, we summoned all Papists and suspected persons to appear in order to tender the oaths" (T.N.A., S.P.35/1, f19r.).He also assured the Government that an account would be sent of what happened because of their implementation of their orders. (T.N.A., S.P.35/1, f19r.).

The danger from Catholics was thought to be a very real one, especially since many had recently arrived at or near to York to attend the race meetings. In any case, York was a great regional social centre, as noted by Daniel Defoe, "there is an abundance of good company here". The number of outsiders would have been considerable. Thus constables were placed at the gates to prevent: "those Papists from giving any Disturbance or going out of the town". (The Daily Courant, 3996, 13 August 1714, P.N. Furbank, W.R. Owens, A.J. Coulson, eds., "Defoe's A Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain", Yale (1991), p273.). To begin with there appears to have been no threat to local order. The Daily Courant could report that two days after the proclamation of the new dynasty had been read in public: "All things continue very quiet here". (The Daily Courant, 3996, 13 August 1715).

This happy state did not last. Sometime between 6 August and late October, 1714, one or more apparently pro-Jacobite disturbances occurred in York. There is no information as to their exact nature. The only reference to them is in a Corporation order given probably in late October. This referred to: "Riots, routs and other disorders which have of late been committed in this city by Day and Night particularly on the Coronation of His Majesty King George". (Y.C.A., F12a, p18).

The Corporation ordered that orders be printed to discourage and suppress such Jacobite activity, though their effect is unknown. Probably the riots died down of their own accord, once such politically charged dates as 20 October (the Coronation) had passed. These riots, however, may not have been entirely political; other riots were economic in cause, but used Jacobitism as an idiom for their protest.

Apart from the disturbances in 1714, there was probably a further outbreak of Jacobite behaviour in 1715. The diary of Mrs Savage, the wife of a nonconformist minister, written in early June states, "this week brings tydings of much disturbances by ye Jacobite mob, great outrages in London, Oxford, York, Manchester..." (Bodleian Library, Department of Western Manuscripts, Ms Eng. Misc.c331, p48). There is no reference to a riot in York in the press, council archives and elsewhere. Possibly it was an attack on a dissenting meeting house, which were attacked in Oxford and Manchester, but there was no evidence that compensation was paid by the Government as it was to like places. It may have been a lesser disturbance, in which there were visual and vocal expressions in public on 29 May (as there were elsewhere) in support of a new Stuart restoration.

During 1714 and 1715, in response to orders from the Privy Council, the Corporation sought to keep an eye on the suspected enemy from within, the Catholics. At first this was relatively mild. On 29 December 1714, 17 out of 65 Catholics in York and Ainsty refused to swear oaths of allegiance. They were fined a total of £2 14s 6d. (Y.C.A. F12a, pviii). On 26 July 1715, the city constables were ordered to return lists of papists within their parishes. The latter were asked to take the oaths again, but this time 34 refused to comply, and were fined the lesser total of £1 3s 6d. (Y.C.A. F12a, pxi-xii). On the same day, an inventory was made of arms and horses belonging to city Catholics: two swords, one gun and three horses being the meagre total. (Y.C.A. F12a pxiv).

On 17 October 1715, after rebellion had broken out in Scotland and Northumberland, 28 Catholics, Non Jurors and others thought to be disaffected, were gaoled, though two days later, 22 had absconded. New warrants were issued to seize them. (Y.C.A. F12a pxvii). The Corporation seemed to be taking its responsibilities seriously, though the competence of its officials was dubious. Regular night patrols were commenced in August 1715. These were made up of the watchman of each ward and one or two city constables, and they were meant to patrol the ward each hour during the night. They would knock on each door and the hour was called out. The system appears to be as much against drunkards and nightwalkers than because of the rebellion. The Corporation was serious about this matter. Negligent watchmen and constables were to be "severely proceeded against". The present decrepit watchmen were to be replaced with new men. The city gates were also to be locked at night. (Y.C.A. House Book, Vol. 41 f150r, 153r).

On 9 September, after the Earl of Mar had raised the Jacobite standard at Braemar, the Corporation sent a loyal address to the King. This was not an uncommon gesture of loyalty among corporations and counties, but the survival of the exact wording of such a missive is rare. Naturally the address gave "the utmost assurances of...unutterable fidelity". It also told of the Corporation's awareness of George's "unquestionable right" to the Crown, and their duty to support him in their own sphere. Indeed: "no activity on our part shall be wanting towards the disappointment of it [Jacobite disorders]". Not only were the popular assemblies so recently seen in the city "so evidently repugnant", but they were carried out by enemies to both the King and "the peace of humane society". The suppression of disorders, therefore, and the belief that George's authority was their best safeguard of Protestantism, seem to be the two main strands of the reasoning behind the Corporation's loyalty. The address finished with the wish that the King would have a long life and prosperous reign, and that there would be a lasting succession of Protestant princes on the throne. (Y.C.A. House Book. Vol. 41. f150r, 156r.)

It was almost six weeks later before the Corporation seems to have taken any further action. There was little that it could do immediately. No local rising seems to have broken out in York or even Yorkshire. The rising seemed confined to Northumberland, at least initially, and then it only broke out on 6 October. As time passed, however, the Corporation appear to become conscious of potential dangers lurking beneath the surface. On 20 October it was noted: "We are frequently alarmed with new Insurrections and Comotions and apprehensive of somemuch nearer than Northumberland." It was proposed, therefore, that the militia should be called out "with all convenient speed" or else some regular military force be sent to York. In the meantime a volunteer company of about 50-60 men was formed. (Y.C.A. F12a, pxix). Given that there were four miles of city wall, it is doubtful whether these men ould have done more than keep a watch at the four principal gates of the city. Furthermore, the city was as, Daniel Defoe noted, "not now defensible as it was then [at the time of the Civil Wars]" It would appear that the Castlegate Guardhouse was to become the central location for these volunteers, and city constables were ordered to deliver coals and candles there. (Y.C.A. F12 p33a, Defoe "A Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain" p274).

Since parish constables were the custodians of parochial arms and their distribution n case of emergencies, it is unsurprising to learn that they were active in this area. The constable of Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate, equipped three men to bear arms, and paid them the generous rate of 12d per day (double that of a soldier0 for eight days service. The total cost to the parish was £4 16s 6d. (B.I.H.R., Y/HTG15, p269). It is unknown whether other constables acted likewise. Possibly each parish provided a quota of volunteers to form the company to help watch over the city, but lacking other constables' accounts it is impossible to be certain.

As in 1745, York was not regarded by the Government as a city that was important enough to send regular troops to defend. Half pay officers from five regiments that had been called up due to the emergency were despatched to York in late September, and may have helped train the volunteers. (The London Gazette, 5367, 24-27 September 1715). In early November, there was some discussion between the Lord Lieutenant of the East Riding, Viscount Irwin, and the deputy Governor of Hull, Colonel John Jones, about the sending of artillery and gunners to York. The despatch of artillery from Hull to York would not have been difficult, because they were connected by water, as Defoe noted. At most this would only have amounted to two gunners who were not sent from Hull until 9 November at the earliest, so they would not have arrived in York until after the surrender of the rebels at Preston on 14 November. (L.A., TN/PO2/2.6).

An instance of signal loyalty was the signing of a loyal association by the Earl of Burlington, Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding. This was signed in the following week by the Lord Mayor, his aldermen, gentlemen, clergy and citizens of York (as well as their fellows in the West Riding), to signify their detestation of the rebellion and their adherence to the King and the Protestant Succession. (The Weekly Journal, 249, 12 Nov. 1715).

When the rebellion was at an end, the Corporation felt able to send an address of congratulation to the King, and this was approved of on 31 May 1716. This was clearly to show their loyalty and to pour scorn on the rebels. The latter had not received much of a castigation in the address of September 1715. The "most monstrous and unnatural Rebellion that perhaps ever stained the Records of Time" had been instigated by traitors, of course, but many of these had been Protestants as well as Catholics. The former were particularly blameworthy, having been unprovoked and being acting contrary to civil and sacred oaths. They had attacked "the best of Kings" and had proved themselves haters of their country. As with the September address, the Corporation wished for a long life to the King and his successors, and that "Party Rage" would die down and that they could look forward to peace, stability and national unity, despite all oppositions. (Y.C.A. House Book Vol. 41, f163r).

The Privy Council appointed 7 June as the day for the official thanksgiving for the suppression of the Rebellion. York Corporation ordered that £40 be spent out of the city coffers on this occasion. (Y.C.A. House Book Vol. 41, f163r). This gesture impressed William Robinson of Newby Hall. On 4 June, he was looking forward to thanksgiving day. He wrote: "I hope to be abroad on the thanksgiving day, our town designs to be very loyall". Apparently, the money paid from public stock for this event was to be spent in: "wine and bickel, in order to intertain ye clergy and gentlemen at ye Common Hall, from whence we are to proceed to the Minster in our formalitys, with drums, trumpets and ye Waits".

There had been a great celebration on 28 May, on the birthday of King George, which had outdone any Jacobite display of 29 May (Restoration Day) . There had been fireworks and bonfires, with the militia officers in their uniforms and other gentlemen and officers making merry at an inn, with an apt name, The George. (L.A. Vyner MSS 6002/13876.) The actual celebration of the defeat of the rebellion came as something of a disappointment to Robinson. It was the last push of the local Jacobite party. On 9 June he wrote that: "In my last to you boasted of our loyalty at York and now I am both ashamed and sorry to let you know we have had any unexpected disturbance". This disturbance consisted of "a little shabby mob who brought out a drest up figure writ upon ye brim of ye hat prisbiterian covenanter, said to be Dr Coweton they shouted High Church". The mob's sport was spoiled by Whig gentlemen, militia officers and others, who dispersed them. Afterwards the Whigs retired, once more, to the George and partook of the refreshments which had been purchased from public funds. Outdoor celebrations included the usual fireworks and bonfires. (L.A. Vyner MSS 6006/13229).

The other arm of the State, the Church, was also active during the crisis. Although the Archbishop was a Tory, he seems to have acted as a fervent defender of the Protestant Hanoverian Succession, as was his more famous successor, the Whiggish Thomas Herring in 1745. This can be seen first in his behaviour during Queen Anne's reign. In 1705 he preached a strongly anti-Catholic sermon on 5 November. This was titled "The continued plots and attempts of the Romanists against the establish'd Church and government of England, ever since the Reformation". (W.Dawes, "The continued plots......" [1709]).Dawes had also written to the presumed Hanoverian successor, Sophia Dorothea, assuring her of his loyalty and that of his clergy in furthering the succession. He wrote on 4 May 1714: "[I] daily and most ardently pray to God, for the health, long life and prosperity of ourself and every branch of your illustrious family amnd particularly that He would guard and maintain your Right of succeeding to the Crown of these Realms as now by law established...not onely myself, but the whole body of our clergy are faithful and zealous". (British Library, Stowe Manuscripts, 227, f16r). His zeal can also be seen in his vigorous role in the military campaign. Whilst Herring was content to remain at York during the '45, Dawes joined forces with the Whig bishop of Carlisle, William Nicholson. The Glasgow Courant reported that: "The Arch-Bp. of York and Carlisle are very Zealous for His Majesties Interest, and are with the Lord Lansdale at the Head of the Volunteers, who have risen in Cumberland and the Neighbouring Countys". (The Glasgow Courant or West Country Intelligencer, issue 4, n. 10, November 1715).

Though the efforts of the two clerics were not to achieve much in military terms, their zeal for their cause is not in doubt. The zeal of the Church was in evidence in other ways. Though there are no surviving sermons for York in 1715-1716, in contrast to those for 1745-1746, the Church was active in other ways. Chiefly, they celebrated the key dates in the Protestant political calendar by the ringing of their bells. Of the three city churches, out of 23, for which itemised accounts survive (St. Johns, St. Martin's cum Gregory, and Holy Trinity Goodramgate), the bells were rung on the following loyalist occasions. For the King's Birthday:3, the Prince of Wales' Birthday: 2, for the news of the victory over the rebels at Preston; 2, and for the double celebration of the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot and the arrival of William of Orange on 5 November; 2. Other events were celebrated by only one church; the Coronation, the anniversary of the accession, for the proclamation of the thanksgiving, on hearing the news of the fall of Perth and one against tumults. (B.I.H.R., Y/J 18, Y/MG 20, Y/HTG 13). Of such bell ringing, the most prominent seems to have been on 5 November, that key date in the Protestant political calendar (celebrating the deliverance of Protestant England from Catholicism in 1605 from Guy Fawkes and William of Orange's arrival at Torbay in 1688), which was publically celebrated. As The Weekly Journal said, it was, "here observed with more than usual solemnity". The day was ushered in with the ringing of bells, especially those of the Minster, "without intermission, only during the time of Divine Service, from Morning till Evening". There was, however, a hint of local division - it was claimed that such ringing was "to the great Mortification of the Tories". (The Weekly Journal, 249, 12 Nov. 1715).

Although there are no surviving sermons from York clergy for 1715-1716, a recent thesis has shown that the overwhelming number of sermons produced by clergy in the south of England during these years were against the rebellion; it is probable that their northern peers acted likewise. (S. Abbott, "The Clergy and the '15", Reading University B.A. dissertation (1997), p34). It has already been noted that the Corporation sent a loyal address to the King on the defeat of the rebellion. So did the Dean and Chapter of York Minster. Unsurprisingly, their emphasis was on religious matters. They declared their abhorrence to the unnatural Rebellion, and assured him of their support, and his undoubted right to the throne. Their reason for giving such assurances was because "we of the clergy are under the most strict Obligations, both of duty and interest". This is to say that they had all sworn allegiances to George I and were also aware that were the Rebellion and Popery to triumph, they as ministers of the Church of England, would be among the first to suffer. They also offered prayers to God that He had granted victory over the rebels. Prayers were also said for George's continued rule and the blessings inherent in this. (The Political State of Great Britain, Vol., XI, p16-17). Much of this was in the same tone and using similar language the address sent by the Corporation, but religious, not civil themes, were stressed.

Anti-popery, then, was the main reason why the Protestant monarch should be supported, and in such strong, unambiguous language as might be expected from those who feared for their current positions as well as clinging to their religious principles. Yet, this appearance of clerical solidarity may have had cracks beneath the surface.

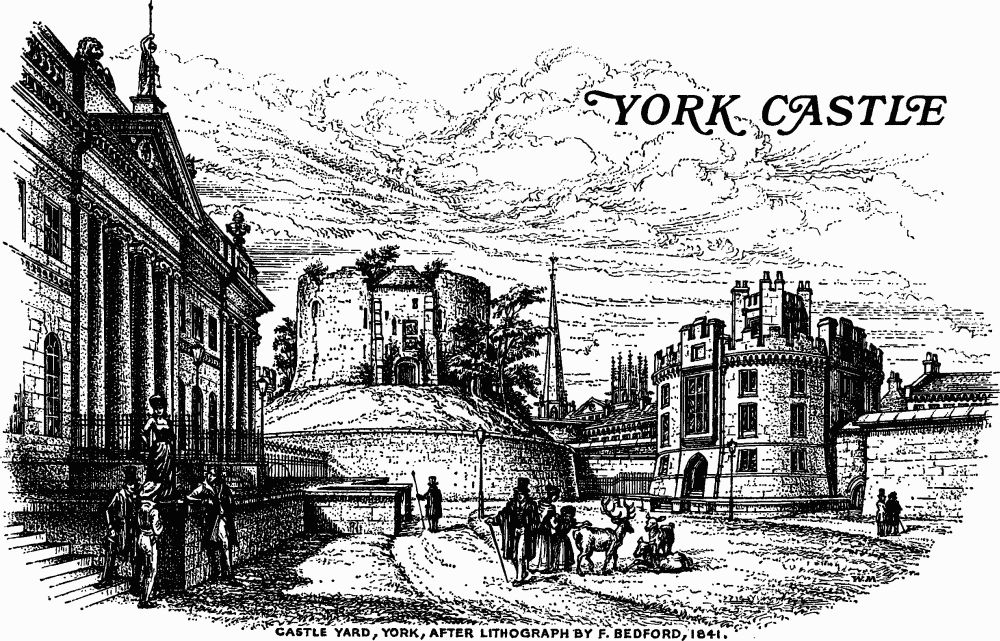

Although trials of Jacobite prisoners were not to take place in York as they were in 1746, York Castle did hold a relatively large number of prisoners on account of the rebellion. Sixty men were detained here, most having been sent there by the county J.P.s. An undated list records that most were incarcerated in October or December, were a mixture of Catholics and "disaffected persons" and included several gentlemen. The Catholics were probably there because they refused to subscribe to the oaths of allegiance as required by Quarter Sessions. Others may have been men suspected as having been with the Jacobites in Lancashire. After all, York Castle was the county gaol. Furthermore, at the beginning of November, a coachman suspected of carrying treasonable papers to edinburgh was sent here. Some left the Castle in January 1716 on bail.

This provoked controversy, for they had been released by order of the deputy Lord Lieutenants, even though Burlington had told them that they could not do so without his consent. Twenty were ordered to be released by an order in Privy Council of 17 April 1716, and another 49 on 29 May, though twenty of those names for both dates are the same. Henry Cutler Esq. was the last to be given his freedom, by an order dating 18 June. (T.H.A., Privy Council, 2/85, p365, 404, 413, 434, L.A., NP1514/9). Two men escaped; they were Catholics and had been detained "upon suspicion of being at Preston". Five guineas were offered for each man's recapture. (The London Evening Post, 1076, 26-28 June 1716).

The end of the Rebellion did not mean an end to Jacobite sentiment at York, according to one observer. Mr. Barlow, writing on 11 March 1719 was convinced that the city was: "a great Rendezvous for all ye chief of the Papists and Jacobite disaffected party who now swarm here to ye degree and are so uppish". Barlow attributed such behaviour to the fact that there was an intended invasion in favour of the exiled Pretender. Violence was feared and Barlow added that he had been told that the Pretender's Health was drunk in the city taverns, even when some of the clergy were present. If clergymen were present, it would indicate that the splits in the York clergy, to an extent, mirrored splits within the Church of England nationally, between the High Church Anglican Tories and the low churchmen, though such a split did not necessarily indicate that the former supported the rebels. He was so concerned that he ended his letter with an entreaty: "I trust speedily some order will be taken with them which I know would be acceptable to all true lovers of their King and Country". (T.N.A., SP35/15, f185r).

Such fears of Jacobitism were not uncommon in the north of England in the years after 1715; Whigs in Pontefract, Leeds and Newcastle had similar concerns, and, though these were not to be realised, they do give an indication of contemporary Whig perceptions of the unsettled nature of the Hanoverian Succession. Jacobitism in York seems to have been largely a popular affair, though some of the middling sort may have been involved, possibly even including some clergymen. However, as in Newcastle, there were no popular disorders during the months of the real emergency of active rebellion in England during October and November 1715. Nor was there to be any like behaviour in 1745. The city elite, whether Tory or Whig, stood with the Corporation and the Church in its opposition to the rebellion. York's official response was to oppose the rebellion, though of course it could not do so in any meaningful military manner. yet it was not apathetic to the dynastic struggle, nor was there any coup d' etat as was suffered by the supporters of James II in the city in 1688. Clearly, as with other corporations, Protestantism and civil order were the priorities of the elites, not rebellion or Catholicism, and they acted accordingly to defend these as much as it was in their limited powers to do so. Since there was no direct military threat, nor any dangerous threat from below, they accomplished such tasks and also appeared zealous in the eyes of those in London. (Ref:- "York and the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715" by Jonathan Oates. York Historian, Vol 24 (2007) p12-18)

Prisoners of the 1715 Jacobite Rebellion

Government forces in Scotland under the command of John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll defeated the Scottish Jacobite army of John Erskine, 6th Earl of Mar at the Battle of Sheriffmuir on the 13th November 1715. Following the battle the Jacobite Scottish army dispersed, with the majority of the rebels returning to their homes.

Between the 9th and 14 November 1715 Government forces in England under General Charles Willis defeated the English/Scottish Jacobite army under Thomas Forster at the Siege of Preston. Almost the entire Jacobite army at Preston was taken captive. In total, seventy-five English and 143 Scottish noblemen and gentlemen surrendered together with some 1,400 ordinary soldiers of whom a thousand were Scottish. Only seventeen men had been killed in the defense of Preston as opposed to 200 on the Government side. In the words of Robert Campbell, Argyle's official biographer, "none but fools would have stayed to be attacked in that position, and none but the knaves would have acted when there as they did". (Ref. "Inglorious Rebellion: The Jacobite Risings of 1708, 1715, and 1719" by Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson page 147)

The prisoners taken after the Battle of Preston were some of the most important captured during the entire rising. This was because of the fact that at Preston, the state captured nearly an entire army, including the leaders by whose authority most of the commoners had come into the rebellion. Additionally, the Preston prisons were immediately available for swift punishment in a way that the prisoners of Sheriffmuir, in the hands of the Scottish authorities, never would be. Finally as the Government realised when given the lists of prisoners, punishing the men taken at Preston represented an opportunity to crush a group that had been a thorn in the side of Whigs, and a perceived threat to the Protestant Succession since 1688, the wealthy, powerful and close knit community of Roman Catholic gentry in northern England. (Ref. "Jacobite Prisoners of the 1715 Rebellion: Preventing and Punishing Insurrection in Early Hanoverian Britain" by Margaret Sankey. Page 17)

When the prisoners had been sorted by rank and distributed into secure quarters, the lords in the best houses, officers and notables in the Mitre, White Bull and Windmill Inns, and the commoners crowded together in the church, the Government began to realise the size of their windfall. The Reverend Robert Patten's (Thomas Forster's chaplain) estimation of the number of prisoners, later printed and widely reported as official, was enormous: 75 English gentlemen, 83 of their servants and 305 English commoners had been taken, along with a larger contingent of 143 Scottish gentlemen and 862 Scottish commoners. (Ref. "Jacobite Prisoners of the 1715 Rebellion: Preventing and Punishing Insurrection in Early Hanoverian Britain" by Margaret Sankey. Page 17)

Three hundred prisoners, including the seven main leaders, Mackintosh of Borlum; William Maxwell, 5th Earl of Nithsdale; James Radcliffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater; Thomas Forster, MP for Northumberland; George Seton, 5th Earl of Winton; William Gordon, 6th Viscount of Kenmure; and William Murray, 2nd Lord Nairne; and the main officers and gentlemen, were separated and marched to London, where the seven leaders were held in the Tower, and the remaining prisoners distributed between Newgate Prison, Tilbury Fortress and the Fleet.

The remaining 1,018 prisoners who had been held in atrocious conditions in the church at Preston were then sent to Lancaster, Chester, Carlisle, Liverpool and York. Some sixty Jacobite prisoners would be held at York Castle Prison until the majority of them were released following the Act of Indemnity (often referred to as the Act of Free Grace and Pardon) July 1717.

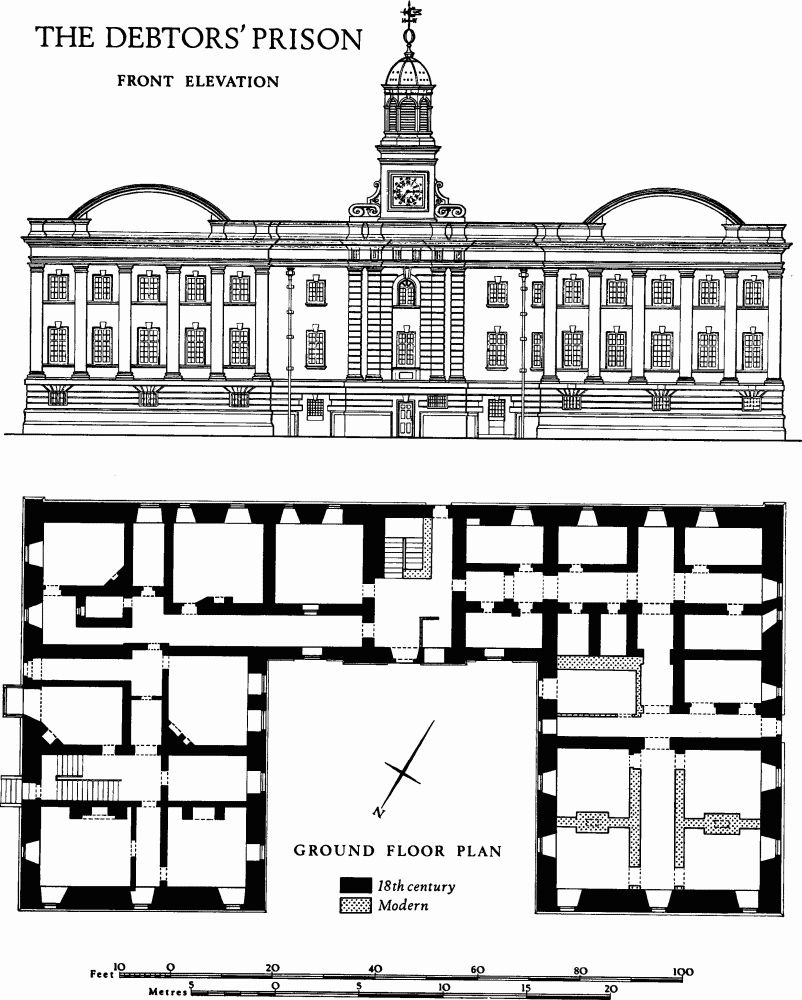

The sixty Jacobite prisoners sent to York were in all likelihood held in the two cells for suspected felons, which were to the rear of the right hand wing of the Debtor's Prison Building. These rooms were 38.5 feet by 24.5 feet and 38 feet by 14 feet. The ceiling height in the larger room was 8 feet and in the smaller room 9.5 feet. Access to these rooms was via a door onto the central courtyard. Both rooms had only two windows each for natural lighting and ventilation. With the arrival of the Jacobite prisoners, these rooms would have been very overcrowded indeed. There being very little natural ventilation conditions would have been very uncomfortable. The air would have been fetid. There was no heating or running water in these cells. Water was provided by a pump in the central courtyard and had to be carried in by the Gaoler's assistants. Sanitation would be a slop bucket, which would have to be emptied each morning.

With sixty Jacobite prisoners, on top of the number of ordinary felons already being held here, conditions would have been dire. By 1715 conditions had become intolerable and when sixty Jacobite prisoners from the 1715 Rebellion were lodged there, a petition was sent to the King from several prisoners for debt in the Castle, requesting "enlargement" (freedom) from prison, as families were in distress and the gaol was full due to the Jacobite Rebellion. The petition was signed by John Ward. Ref: Folio 136 SP 36/80/3/136 held in the National Archives.

Overcrowding was a common problem, especially as throughout the 18th century there was no regular programme of shipping off the transports and their numbers often swelled accordingly. The Prison authorities were paid four pence per day for the upkeep and food for the prisoners. With the influx of the Jacobite prisoners this meant some expense for the Government.

The Government was also anxious to empty the area's jails of anyone who was taken up by mistake, so that the limited room could be used to house men who were known to be Jacobites. Charles Townshend, the Secretary of State, personally ordered the release of four men, one of them a "poor vagabond", another a man who inadvertently talked to the rebels and was arrested as a rebel himself. Local authorities were surely doing the same kind of screening themselves to sort out men they knew to have been mistakenly imprisoned.

In York, seven men, six of them personal servants of known rebels, were released as too unimportant to keep, while Christopher Small, a fugitive debtor from London, who was caught up in the dragnet, was released because York had no interest in prosecuting a London crime! (Ref: SP44/118/159; SP44/118/178; SP44/118/200; Faithful Register, 398. (Ref. "Jacobite Prisoners of the 1715 Rebellion: Preventing and Punishing Insurrection in Early Hanoverian Britain" by Margaret Sankey. Page 49).

Transportation:-

By January 1716, the British Government had incarcerated more than 1,200 prisoners taken before and after the capitulation at Preston alone. (Baga de Secretis Abstracts, KB33/1/5/65-66. There were 22 prisoners at Lancaster, 157 at Wigan, 467 at Chester and 446 in Preston and 60 at York). Cached in makeshift jails and castles across northern England, each man was costing the authorities 4d per day to feed in bread, cheese and beer. Cost considerations apart, supplying such numbers stretched the capabilities of the local economy, especially during the winter, and so something had to be done with them reasonably rapidly. Thus the prisoners had become a serious problem for George I and his council. Leaving them in prison strained relations with the local authorities (who had to feed and house them) and posed the threat of epidemic disease, and, too, provided a focus for the disaffected and Catholic, who were gathered around the jails and sending in blankets and food parcels (Ware, Lancashire Memorials, 163). On the other hand, releasing even these prisoners, most of whom were commoners left behind when the rebel leaders were sent to London after the surrender, did not strike the deterrent note the Government needed.

The central authorities had a range of historical precedents to choose from in planning the punishment of the prisoners. The harshest was the stance taken by Elizabeth I after the Northern Rising in 1569, when the Queen insisted that more than 450 rank-and-file rebels be executed, the poorest put to death summarily under martial law, those with estates tried by jury to allow legal confiscation of their property.

The acquisition of substantial overseas colonies and the subsequently successful program of transporting poor children and undesirable vagrants to Virginia, beginning in 1617, created a more humane alternative that was first used during the Great Civil War. The Commonwealth, unwilling to release the large numbers of royalist prisoners taken at the first battle of Preston (1648), Dunbar and Worcester, but unable to afford their upkeep in English jails, transported them to New England, the Caribbean and Ireland, although it was careful to specify that the prisoners should never go to places where they might be used against the Commonwealth. (Williams, The Later Tudors, 258: Abbot Emerson Smith, Colonists in bondage: White Servitude and Convict Labor in America 1607-1776 [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1947], 152, 154.)

James II used transportation to dispose of 522 participants in Monmouth's Rebellion in 1685, although this was paired with the harsh sentences meted out by Judge Jeffrey's 'Bloody Assizes'. The King allowed favoured courtiers to contract for shiploads of prisoners and profit from the sale of their indentures in the West Indies, and to protect their investment, stipulated that any ship's captain or purchaser of an indenture who freed one of the rebels would be fined £200, be imprisoned for a year and be barred from holding public office in the islands, while escaping rebels faced a sentence of 39 lashes, time in the pillory and a brand of F.T., meaning 'fugitive traitor'.

A popular pamphlet, A Relation of the Great Suffering and Strange Adventures of Henry Pitman (1689) described the islands as a death trap of disease and back-breaking work, and detailed the author's desperate attempts to bribe his way to freedom. There was, however, an ideological difficulty here. For all good Whigs, James II's exploitation of this option was standing proof of his tyrannical nature. (Smith. Colonists in Bondage, 193; C.H. Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate [Edinburgh: T and A Constable, 1899], 189, 192).

In dealing with the Jacobite prisoners in 1690-91, William and Mary were more interested in removing the rebels from Ireland than in swingeing punishment. The Treaty of Limerick allowed the prisoners to leave Ireland with their families and personal property for any destination outside of the British Isles. Any who wished to enter military service in France were not only given leave, but supplied with free transport. Because of these liberal provisions, more than 12,000 Jacobites entered the army of Louis XIV and immediately fought against William III in Europe, making this a procedure George I's Government was disinclined to follow. (J.G. Simms, Jacobite Ireland [Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2000], 159-60).

Faced with a prison crisis that daily grew more difficult to resolve (as local authorities, faced with mounting debt, clamoured for money and/or relief), the ministry decided on a compromise that tended towards the Great Civil War precedent.

Putting this policy in practice, however, proved rather more difficult than George I and his councillors anticipated. When all the trials were over, the Government offered transportation to the plantations, which the King apparently thought meant the West Indies, in exchange for a pardon conditional on the men remaining overseas for the rest of their lives. (Abbot Emerson Smith, "Transportation of Convicts to the American Colonies in the Seventeenth Century" in The Peopling of a World, ed. Peter Charles Hoffer (New York: Garland, 1988), 237).

This seemed to the King and his Government to be both a humane and sensible option for dealing with men who, according to the law, should all have been hung, drawn and quartered, and their posterity ruined by the confiscation of their property. Unfortunately, this seemingly simple solution was soon entangled in a thicket of legal problems assiduously raised by the prisoners in an effort to prevent their deportation. For although transportation had existed since the establishment of English colonies, and had its origins in the 1547 Vagrancy Act, itself inspired by Sir Thomas More's Utopia, (Robin Blackburn, 'The Old World Background to European Colonial Slavery' in The Worlds of Unfree Labour, ed. Colin A. Palmer (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998), 105-6), transportation was a sentence that could only be applied by judges, not ordered.

A prisoner had to request transportation and could not be sent out of the country involuntarily, a stricture of English Common Law which had only twice been violated, and then briefly, in 1666 and 1670. Secondly, transportation did not exist in Scottish Law, Scotland having no plantations into which it could send prisoners. Banishment from Scotland was the maximum such sentence in Scottish Law, although those so banished could be executed for returning without permission.

Scottish prisoners quickly seized on this judicial conflict to protest that they could not be held to English Law when Scottish Law did not contain provisions for similar punishment. (Smith, 'Transportation of Convicts', 232) In addition, the Government's insistence that the men leave under indenture could not be legally enforced. Indentures existed to finance the transportation of emigrants crossing the Atlantic, not as a punishment. Most of those who requested transportation entered indentures for the same reason as their non-felonious fellow emigrants: they lacked the fare required to get out of Britain. To force the prisoners into indentures violated statute law in the form of the Habeas Corpus Act, a point which did not escape the notice of the prisoners themselves. (Charles Edward Gillam, 'Jailbird Emigrants to Virginia' Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 52 (July 19440, 180).

While waiting for the 'grateful' prisoners to ask for transportation, the Government nonetheless proceeded with the public punishment of the 33 men condemned at the Liverpool and Preston trials. When even this failed to inspire petitions for transportation, the infuriated ministry instructed the jailers to intimate to the prisoners that further reluctance to accept the King's gracious clemency would provoke more trials, not just confined to those who had drawn lots and remained untried, but of all those against whom the Government had substantial evidence, and that more executions were sure to follow. (Townshend to Sir Francis Page, 29 January 1716. SP 44.118.176). Additionally, the jailers applied physical coercion to the obstinate, as described by an anonymous prisoner at Chester Castle who refused to sign his indenture "whereupon we were severely threatened and without getting liberty to return to our rooms for our bed clothes and linen, we were all turned into a dungeon or little better, and fed only with bread and water". (Hugh Paterson, Leiden, to Mar, 23 June 1716, HMC Stuart II, 232-3).

The following week, Major Solomon Rapin, the supervising 'commander' of the prisoners, compiled two lists, finding that of the 1,200 plus men, 206 refused to petition for transportation, while only 116 accepted. The rest kept their own counsel, preferring not to commit themselves. (Prisoners Petitioning for Transportation, 5 February 1716, KB33/1/5/19; Prisoners Refusing Transportation, 6 February 1716, KB33/1/5/16.).

The reason for this extraordinary show of resistance lay in the prisoner's folk-memory of the treatment of Scottish rebels by the Commonwealth after their defeat in 1650. Despite the Rump Parliament having already sent hundreds of English royalists as indentured servants to the West Indies and New England, the Protectorate was puzzled as to what they could do with people, "so poor and idle that they cannot live unless they be in arms". (Monck to Cromwell, 2 May 1654, in Firth Scotland and the Protectorate, 100).

A plan to "make merchandise" of the prisoners by sending them into mercenary service with the Dutch or Holy Roman Empire against the Ottoman Turks came to nothing, frustrating Cromwell until he realised the prisoners' value in his negotiation with various Scottish leaders. Magnates like Atholl and Seaforth ultimately negotiated terms with the Protectorate that included freedom for their vassals, in many cases literally rescuing them from the holds of ships preparing to transport them. (Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate, 81).

Many prisoners in 1716, particularly among the Scots, accordingly hoped that when leaders like Huntley and Seaforth made terms, these terms would include their release. Unbeknownst to the prisoners, Argyll, while conducting the campaign in Scotland, had in fact, been specifically forbidden to enter into terms with any of the rebel leaders. Furthermore, the terrible fate of the rebel prisoners transported to the West Indies after Monmouth's rising had also passed into popular folklore, which added considerably to the Jacobite prisoner's disinclination to accept George I's 'clemency'.

Myth-history and folklore aside, the prisoners had strong practical incentives to be recalcitrant. Obviously, those with families, wives and children faced what would probably be a permanent separation from their loved ones, and both they and many of their unmarried fellows wanted to avoid leaving their homeland. Because of the Government's original offer, most of the prisoners and their families also believed that they were going to Jamaica or the West Indies, generic designations for what everyone knew were the malarial cane fields of the islands, where the prisoners would work as slaves alongside the Africans whose terms of service were for life, although given the mortality rates prevailing on Caribbean plantations, seven years' servitude in any form was likely to prove a death sentence.

Despite continued resistance, transportation began with the departure of the Scipio on 30 March 1716, bound for Antigua carrying the first 95 'volunteers', many of whom had actually been tried and condemned to death and gained a conditional pardon by their acceptance of transportation. By then convinced of the seriousness of their situation, the remaining prisoners began writing to anyone they knew who had connection to the Government to ascertain their chances of avoiding execution of sentence without transportation.

Ultimately, by August 1716, 638 men consented to transportation and duly departed for the colonies on ten ships chartered by Sir Thomas Johnson, who contracted with ship captains bound not just for the islands, but for Virginia, Maryland and South Carolina. (Transcript of a letter written by James Stanhope (Secretary of State) at Whitehall to the Commanding Officer of his Majesty's Forces in Liverpool. It gives orders for the transportation of Jacobite prisoners in Liverpool Castle to plantations in America and provides instructions for the care of sick prisoners, 29 February 1716 [SP 35/5/13).

"Whitehall February 29th 1715

I am commanded to signify [show] his Majesty’s pleasure to you that you should deliver to Sir Thomas Johnson, or Mr. Richard Gildart & Son: Trafford Merchants in Liverpoole such of the Prisoners in the Castle of Liverpoole , in order to their being transported to some of his Majesty’s Plantations in America, as have subscribed [signed] the Petition inclosed and are in a fair state of health- taking care that all the Prisoners so to be transported, do in the [presence] of the Mayor, or other Cheife Magistrate of the Sea Port Town, where they shall be embarked [taken on board], execute Judicature [hold trials] in due form; thereby obliging themselves to serve in the Plantations for the term of Seven years from the time of their Arrivall there.

You will likewise give such assurance to the magistrates & the Persons concerned in the receiving the said prisoners, as shall be judged necessary for putting them on board the severall ships to which they shall be consign’d with the greatest case of safety. As such of them as are not in a condition to be transported in regard to their health, you are to take care that they be as soon as possible taken out of their places of confinement in order to have the benefit of the air, with these restrictions that it be within the castle walls & at proper times, and with proper Guards, so as to prevent their making Escapes.

It is likewise his Majesty’s Pleasure, that the Places of their Confinement [prison cells] should be cleaned & proper medicines be administered [given] by the Physicians [doctors]and apothecarys [chemists] of the Town to such of them, whose cases shall require it, so as to prevent any contagious Distemper [disease] getting amongst them the charge where of shall be reimbursed [paid] by his Majesty’s order and as such Prisoners shall recover their health, you are to Deliver them in the same manner as is above mentioned in order to their being likewise Transported. After the Prisoners are embarked you are to transmit [send] back to me this originall Petition.

It is His Majesty’s Pleasure [wish], that Charles King one of the Prisoners at Liverpoole, who has sign’d the Petition, should not be delivered with the rest to be Transported, but that he should be taken out of Prison, & quartered in a private Lodging under a Guard.

I am Sr. Your most humble Servant, James Stanhope

Commanding officer of his Majesty’s fortress in Liverpoole"

TS 20 47 3 [Public Record Office, Treasury Solicitor] Cover sheet, pp 7, 7reverse and 8. Warrant Sr. Thos. Johnson for Transporting Rebel Prisoners. (Copy)

Whereas Sr. Thomas Johnson of Leverpoole in the County of Lancaster Knt: being under an Agreement wth. us persuant to Articles in that Behalfe bearing date the 16th Day of April 1716 to transport or carry at his own proper Cost & Charges to some of his Maj. Plantations in America such Rebels or Prisoners as were or should be delivered or offered to be delivered to him or his Servts. at Liverpoole from any of the Goals of Chester, Leverpoole or Lancaster We in Consideration thereof did by the same Articles Covenant & Agree on his Maj: Behalf that the sd. Sr Thos. Johnson should recieve and be paid 40 sh. for every Rebel or Prisoner that was or should be so delivered to be transported upon producing proper Certificates from the Mayor of Leverpole as the Collector or Searcher of ye Port of Liverpoole of the sd. Rebels or Prisoners being shipped on Board of his Ships in & by the sd. Articles amongst other things relation being thereunto had may more fully appear.

These are by Virtue of his Maj. Genl. Tres patents Dormant bearing date 14th Day of August 1714 to pray and require your Lordship to draw an Order for paying unto the sd. Sr. Thomas Johnson or his assignes the sum of 278L 00sh together wth. the sum of 1000 already issued to him by way of Advance upon the Contract or Agreemt. is in full of the sd Allowance of 40sh for 639 Rebels or Prisoners so shipped for Transportation according to the annexed Certificates attested by the Mayor of Liverpoole & the Collr. or Searcher there as by the said Articles is directed, that is to say:

30th March 1716 shipped on Board the Scipio Frigate Capt. John Scraisbrick Commander for Antigua 96 Rebels nil. at 40sh each amount to . . . . . 190

21st April 1716 shipped on Board the Wakefield Capt. Thos. Beck Commander for South Carolina or Rebels nch. at 40sh each amount to . . . . . . 162

26th April 1716 shipped on Board the Two Brothers Edward Rathben Commander for Jamaica 47 Rebels or Prisoners nch. at 40sh each amout to . . . . . 94

7th May 1716 shipped on Board the Susannah Capt: Thos. Bromhall Comander for South Carolina 104 Rebels or Prisoners at 40s each amount to . . . . . 208

24th May shipped on Board the Friendship Capt. Michael Mankin Commander for Maryland or Virginia 80 Rebels or Prisoners nch: at 40sh each amount to . . . . . . 160

25th June 1716 shipped on Board the Hockenhill Capt. Hockenhill Comander for St Christophers 30 Rebels or Prisoners nch.at 40s each amount to . . . . . 60

29th June 1716 shipped on Board the Elizabeth & Anne Capt. Ed: Trafford Commander for Virginia or Jamaica 126 Rebels or Prisoners nch. at 40s each amount to . . . . . . 252

14th July shipped on Board the Goodspeed Capt: Smith Comander for Virginia 54 Rebels or Prisoners nch: at 40sh each amount to . . . . . . 108

15th July 1716 shipped on Board the Africa Gally Rd. Cropper Comander for Berbadoes one Rebel or Prisoner nch at the same rate amon. to . . . . 2 Eod Die shipped on Board the Elizabeth & Ann Capt. Ed. Trafford Commander for Virginia one Rebel or Prosoner nch at the same rate is . . . . . . 2

28 July shipped on Board the Goodspeed Arthur Smith Mar. for Virginia two Rebels or Prisoners nch. at the same rate amount to . . . . . 4

31 July 1716 shipped on Board the Ann Capt: Robt. Wallace Commander for Virginia 18 Rebels or Prisoners nch. at the same rate amount to . . . . 36

1278 From nch: to be abated the Sum advanced and paid as aforesaid . . . . . . 1000 Then remains . . . . 278

Notwithstanding nch. Paymt. the sd. Sr. Thos. Johnson is by the sd Articles obliged to produce Certificates signed by the Govn. or Governors of the said Plantations of the Landing of the sd. Rebels or Prisoners in the sd. Plantations or upon any of their dying by the Way an Affidavit of such Death And let the sd. Order be satisfied out of any his Maj. Revenues being & remaining in the Receipt of the Exchequer applicable to the Use of the Civil Government. And for so doing this shall be your Warrant

Whitehall Treary Chamber

25th March 1717 R. Walpole Wm Sr. Quintin Torrington R. Edgcumbe

In order to speed the process, Johnson left the indentures in the hands of the captains, who were paid 40 shillings, a head in advance to transport the prisoners, and who would pocket the indenture's market value when it was sold. Stanhope, hoping to guarantee that the rebels arrived at and remained in the colonies, sent stern warnings to all the governors of the ships' destinations that the men were to enter into indentures, and that they were to be guarded vigilantly and exact lists returned to London naming the purchasers of the indentures. (Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia, ed. H.R. McIlwaine, vol. 3 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1928), 428-9; Calendar of State Papers: Colonial Series, America and the West Indies, ed. Cecil Hedlam, vol. January 1716-July 1717 (London: HMSO, 1930), 128).

Stanhope's precautions hint at the ministerial misgivings about the likely outcome of the transportation policy and such fears proved well founded. No sooner had the process of transportation begun before prisoners began to escape and to lay elaborate plans to avoid fulfilling the terms of their sentences. It was common knowledge amongst the prisoners that the going rate to buy one's freedom from a ship's captain was £80, a fact which won Andrew Hogg his freedom after he pointed it out to the authorities, acting out of resentment that he could not afford it himself. (Paul Methuen to the Lords of the Treasure, 9 August 1716, SP44/147/28-9).

("Jacobite Prisoners of the 1715 Rebellion: Preventing and Punishing Insurrection in Early Hanoverian Britain" by Margaret Sankey [Ashgate Publishing Limited, Hampshire 2005] Page 59-64)